Interracial Double Portraits

Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray

and the attribution to David Martin (1737-1797)

By Valeria Vallucci

David Murray, Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, late 1770s, Scone Palace, Perth

The recent Royal Academy exhibition Entangled Pasts 1768-Now: Art, Colonialism and Change was part of a global effort by art institutions to re-examine and re-interpret both history and art in light of new understandings of colonialism. The exhibition explored the Royal Academy’s own associations with British imperialism and the relationship between ‘modernity and coloniality.’[1] It presented an impressive range of contemporary artifacts and historic paintings that have been recognised around the world as providing valuable insights into Black British history and the Atlantic slave trade. Included amongst them was a portrait of the late 1770s by David Martin (1737-1797) depicting Dido Belle (1761-1804) and Lady Elizabeth Murray (1760-1825). The portrait is one which the gallery is very familiar with; in 2018 Philip investigated and confirmed its authorship on an episode of BBC’s Fake or Fortune? (Series 7). On loan from Scone Palace (Perth), the Scottish seat of the Earls of Mansfield, it once hung at Kenwood House and was loosely attributed to Johann Zoffany (1733-1810). Dido and Elizabeth were great-nieces to the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793).

Dido was the daughter of Admiral Sir John Lindsay (1737-1788), Commander-In-Chief of the British Navy, and an enslaved woman called Maria. She was brought up between Kenwood House and Bloomsbury by the childless Mansfields together with her cousin Lady Elizabeth, who was also a maternal orphan. The two girls kept each other company, were educated together, but had different roles and allowances within the family. Dido contributed to the running of the house, sometimes acting as secretary to her great-uncle and managing the dairy and poultry yard.[2] An obituary printed in 1788 stated that Dido’s ‘amiable disposition and accomplishments have earned her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants’.[3]

At the Royal Academy exhibition, the double portrait was shown in the section ‘Sites of Power: Conflict and Ambition’ to highlight the ambivalence of Lord Mansfield’s attitude to slavery.[4] Politicians and actors admired Mansfield’s prodigious oratorical skills. He was also highly respected by tradesmen for his swiftness of action and common sense.[5] During the James Somerset case of 1772 he famously denounced slavery as being ‘so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it’.[6] Yet he was always careful not to damage businesses that traded overseas. This conflict is explored well in Belle (2013), the romantic period drama directed by Amma Asante based on Dido’s story, which focuses on Lord Mansfield’s ruling in the Zong case (1783) and on the double portrait as evidence of his thinking.[7]

The double portrait received considerable media attention after the release of Belle (2013) and the publication of Paula Byrne’s Belle: The True Story of Dido Belle (2014). The rediscovery of Dido Belle’s story – the daughter of a slave who became a member of an aristocratic British family – inspired a wider conversation about race, slavery, and abolition. The painting, in turn, is now recognised as being of national historical importance.

After receiving so much exposure, in 2018 the Mansfield family engaged Philip and the Fake or Fortune? team to try and establish the correct attribution of the portrait. After extensive research in the Mansfield Archive, and thanks to in-depth stylistic and forensic analysis, they established that the portrait was painted by the Scottish portraitist David Martin (1737-1797).[8]

An inventory dated 1796 shows that just three years after Lord Mansfield’s death, the portrait was no longer on display at Kenwood House and its artist was completely unknown.[9] Early twentieth-century inventories do not even mention Dido Belle by name, suggesting she had been completely forgotten.[10]

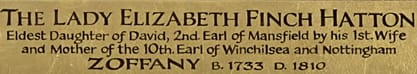

When the portrait was later reframed at Scone Palace the accompanying plate erased her completely:

Still taken from BBC One, Fake or Fortune?, ‘A Double Whodunnit’, Series 7, Episode 4.

The breakthrough came when Philip inspected Lord Mansfield’s private account books from the late eighteenth century. These revealed a payment of £200 to David Martin on 8th October 1776. By comparing the portraitwith another portrait by David Martin in the Mansfield collection, Lady Margery (1760s), he noticed a series of striking similarities.

For instance, the small colourful flowers catching the light on Lady Elizabeth’s hair echo Lady Margery’s hair adornments. Both ladies are painted with bright red ruby lips and elongated faces. As Philip explained, portrait painters of the time tended to impose their own ideas of how a subject should look, and this is an example of Martin’s ideas on how to paint aristocratic ladies. He also noticed similarities in the embroidery, translucence, and folds of the gauzes in both works, as well as the playful positioning of Dido’s right hand which recalls that of Lady Margery’s in her portrait.

After Philip established that an attribution to Martin was highly possible, specialist conservationists from the University of Northumbria were called in to collect samples from both portraits. They found that the white paint and the vermillion in both paintings were an exact match. As a result, Brian Allen, an authority in eighteenth century British portraiture, endorsed the attribution. Allen was particularly convinced by the distinctive handling of the silks, satins and muslins which he considered an influence from Alan Ramsay, who taught Martin.

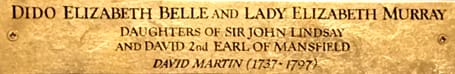

Since this endorsement, the portrait has received a new name plate which tells a more complete story of the work and those involved in its creation.

Detail of David Murray's Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray, late 1770s.

The subject of affectionate interracial relationships in art (as opposed to the servant-master relationships such as the one in Reynolds’s Portrait of George Prince of Wales)[11] is of great interest to the team at Philip Mould & Company, who have had the privilege of handling two early nineteenth-century interracial double portraits: a French miniature and a Northern American oil. Both works have since sold to important public collections in the USA. These works are unique and significant and like Martin’s double portrait, are infused with multiple, complex layers of history and symbolism. They offer fascinating insights and prompt questions about identity in the wake of colliding cultures; themes which in an increasingly globalised, interconnected world are more relevant now than ever before.

[1] Entangled Pasts 1768 - Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, Royal Academy of Arts, London 3 February - 28 April 2024, pp.6 and 12.

[2] Kenyon Jones, C. (2010) ‘Ambiguous Cousinship: Mansfield Park and the Mansfield Family’ in Persuasions On-line, vol. 31, no.1. Available at: https://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol31no1/jones.html? (Accessed 17 April 2024).

[3] London Chronicle, 7 June 1788. Quoted in Byrne, p.210.

[4] Entangled Pasts 1768 - Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, p.65.

[5] Byrne, pp.111-120.

[6] James Somerset was a young African slave purchased in Virginia in 1749 by merchant Charles Stewart. In 1769 Stewart brought Somerset back to London. Soon afterwards Somerset was baptised and decided to leave his master. At the end of 1771, under Stewart’s orders, Somerset was kidnapped to be sent back to Virginia as a slave. Lord Mansfield ruled that it was unlawful to transport Somerset out of England against his will. His decision interpreted as a declaration that slavery was unlawful in England, boosting the abolition movement on both sides of the Atlantic. Many contemporary commentators believed the Somerset case was influenced by the presence of Dido Belle in Lord Mansfield’s household. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/kenwood/history-stories-kenwood/somerset-case/ (Accessed 17 April 2024).

[7] In 1781, because of a shortage of water, more than 130 enslaved African people were murdered by the crew of the Zong by being thrown overboard in chains. Zong’s owners claimed insurance for their maritime commercial loss, but the insurers refused to pay. Lord Mansfield ruled the loss was the result of a series of errors for which the crew was responsible. The case established that enslaved people could not be treated as ‘chattel’ and was a key moment in the development of the abolition movement. In the movie Belle, with considerable artistic licence, Dido learns from Mr Davinier, a passionate abolitionist lawyer, that for powerful traders, enslaved people can be worth more dead than alive, so human “cargo” should not be insured. Meanwhile, Lord Mansfield has to judge if such violent acts are ‘truly necessary’ for the safety of a ship. In the film this creates tension between Lord Mansfield and Dido. She becomes convinced that, when push comes to shove, existing rules and social norms are ‘inconsequential’ for her uncle - and his commission of Portrait of Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray proves this.

[8] BBC One, Fake or Fortune?, ‘A Double Whodunnit’, series 7 episode 4. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0bj6gm7 (Accessed 11/04/2024).

[9] ‘Lady Elizabeth and Mrs. Davinier, without a frame’. Mansfield Archive, Inventory of Household Furniture etc at the Earl of Mansfield’s House Kenwood (1796), p.37. In 1793 Dido married John Davinier, a gentleman’s steward.

[10] ‘Portrait of Lady Finch-Hatton, eldest daughter of David the 2nd Earl of Mansfied, by his first wife, and mother of the 10th Earl of Winchelsea and Nottingham, seated in a garden with an open book and a negress attendant’. Mansfield Archive, Inventory of Sevres, Dresden & Other China & Ornamental Articles Being in Kenwood, Hampstead, The Property of The Right Hon.ble The Earl of Manfield (1904). In the 1910 inventory Dido Belle is not mentioned at all in the description of the painting.

[11] Entangled Pasts 1768 - Now: Art, Colonialism and Change, cat.11.